Measure the equity return impact of variable-cost ESG initiatives and their influence on portfolio company revenue.

The site’s value creation models explain how private equity returns are driven by changes in portfolio company P&Ls, capital structures, and market conditions. The same mathematics can be used to methodically examine the equity value impact of certain Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives.

Quantifying ESG Factors

Analysts can easily quantify ESG initiatives that have predictable and measurable influence on portfolio company income statements, balance sheets, and valuations. This case study illustrates two examples:

Gross Profit Margin (COGS) Impact

Consider a commitment to using more ecologically sustainable inputs in a manufacturing process or sourcing “fair trade” inputs from regions where workers earn higher wagers. By increasing the variable costs of delivering products or services to customers, such ESG initiatives will generally reduce a company’s equity valuation and reduce investor ROI.

Revenue Impact

Different ESG initiatives can either increase or decrease revenue, and that will move the company’s equity valuation and investor ROI in the same direction. For example, refusing to sell certain products may reduce revenue. This case study considers a company whose ESG efforts allow it to increase revenue by selling more units, increasing unit price, or both.

ESG Initiative Impact on Capital Structure and P&L

Consider a $100.0 company that is capitalized with $50.0 of total equity and $50.0 of net debt. It has $80.0 of revenue, $48.0 of gross profit, and $28.0 of SG&A, providing $20.0 of EBITDA. Prior to the ESG investment, the company has a gross profit margin (GP/R) of 60.0% and an operating expense margin (SG&A/R) of 35.0%. The company’s $100.0 enterprise valuation is 5.00x its EBITDA.

Assume that certain ESG initiatives reduce the company’s gross profit margins by 5.0%, but the company’s cleaner and greener positioning allows it to sell more units and increase revenue to $90.0. Will these ESG initiatives cause shareholder equity to increase or decrease?

A company with $90.0 of revenue and a 55.0% gross profit margin would have gross profit of $49.5. If SG&A remains $28.0, then EBITDA would increase from $20.0 to $21.5. The post-ESG enterprise valuation is 5.00x this $21.5 of EBITDA, or $107.5. Net debt remains unchanged, so total shareholder equity increases to $57.5. Thus, the ESG initiatives provide an equity gain of $7.5, or 15.0%.

The causes of equity value creation can be quantified by comparing the pre-ESG (t1) and post-ESG (t2) metric absolute changes, averages, and equity return multipliers, as above.

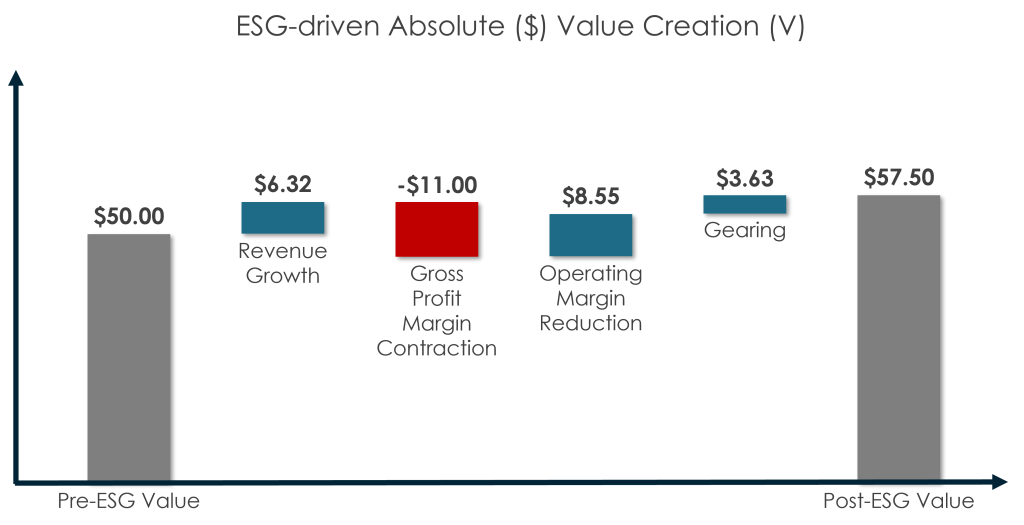

ESG-driven Absolute ($) Value Creation

The Derivative Model provides the quickest path to measuring absolute ($) value creation. This time, four value drivers are material, including Revenue Growth (VME), Gross Margin Expansion (VGME), Operating Margin Reduction (VOMR), and Gearing (VGEAR). Other value drivers, like Multiple Expansion (VME) and Cashflow Generation (VCF), are $0.0 because there is no change in valuation multiple or net debt.

Revenue Growth (see Module 11), driven by consumer demand for more ESG-aligned products, is equal to the product of the +$10.0 revenue increase and the average holding period EBITDA margin, valuation multiple, and equity ratio:

![]()

Gross Margin Expansion (see Module 12), driven by higher variable costs, is equal to the product of the -5.0% gross profit margin decrease and the average holding period revenue, valuation multiple, equity ratio:

![]()

Operating Margin Reduction (see Module 12), driven by higher revenue on fixed SG&A, is equal to the product of minus the change in the operating expense margin (-3.9%) and the average holding period revenue, valuation multiple, equity ratio:

![]()

The remaining value creation is explained by Gearing (see Module 08), which represents debt’s amplification of the equity gains and losses, which are caused by the three value drivers above. Gearing is the product of the change in enterprise valuation and average holding period debt ratio:

![]()

These four value drivers sum to the total equity value change of $7.5, and completely bridge the gap between the pre-ESG equity valuation of $50.0 and the post-ESG equity valuation of $57.5.

![]()

![]()

Identifying the Break-even Point

What amount of Revenue Growth would be required to make up for a certain increase in variable costs, whether that be from ESG or other initiatives?

This question is best answered with the Logarithmic Model, where a deal’s Gross Multiple of Invested Capital (MOIC) is expressed as a function of pre-ESG (t1) and post-ESG (t2) revenues (R), EBITDA margins (EM), valuation multiples (M), equity ratios (ER), and Fund or GP ownership percentages (φ), where:

![]()

For a break-even analysis, the analyst seeks the combinations of variables that cause the MOIC to equal 1.0. Several variables are 1.0 because of constraints built into the example. Both M2/M1 and φ2/φ1 go to 1.0 because no changes are made to the company’s valuation multiple or the GP’s ownership percentage. Further, the only reason that the company’s equity ratio would change is because it is downstream from revenue and EBITDA margin changes so, for the purpose of a break-even analysis, that can be set to 1.0 as well. This leaves only the following variables:

![]()

Because the product of revenue and EBITDA margin is always EBITDA, the expression above must be equal to E2/E1. This means that an ESG initiative will be break-even whenever the EBITDA after the ESG investment is equal to the EBITDA before the ESG investment, where:

![]()

EBITDA can be expressed as a company’s gross profit minus SG&A but, in this example, SG&A was unchanged, so SG&A1 = SG&A2, and:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Gross profit can be expressed as the product of a company’s revenue and gross profit margin. Making this substitution and solving for R2 provides the post-ESG revenue needed to make up for any given change in the portfolio company’s gross profit margins, where:

![]()

The absolute revenue change (ΔR) required to compensate for changing gross profit margins can be determined by replacing R2, with R2 + ΔR, where:

![]()

In the example above, a gross profit margin drop from 60.0% to 55.5% will require at least $7.27 of additional revenue to reach break-even, because:

![]()

Resources

ValueBridge.net Modules:

- 08. Gearing and Cashflow in an LBO

- 11. Revenue Growth and EBITDA Margin Expansion

- 12. Gross Margin Expansion and Operating Margin Reduction

Additional Resources

Also see the ESG in Private Equity video and related content at AUXILIA Mathematica.

Please log in access additional content. Not a subscriber? Sign-up today!.